Architecture Birth Vol.3 Physical experience Group image and kinetic energy, 2018 - 2021 Read more {{currentSlide}}/{{total}}

Buildings themselves do not have emotions, but through spatial design, they can trigger unforgettable interactive experiences that engage people’s senses. This makes architecture more than just an abstract space; it becomes a human-centered “place.” A good building is democratic and anonymous. It transcends time and origin, prioritizing authentic human experiences. In this process, the building fulfills its own purpose.

Zhang Di:

Since the first day I became an independent architect, I have believed that people are the most important factor in architecture. When I mention people, I refer to the users who occupy and utilize the space. Therefore, I consider architecture as a fortunate profession because we have the opportunity and potential to create a place that can impact a group of people or an individual to some extent. I believe that a person’s emotions and state of mind fluctuate, and I want to respond to these states so that they can experience and feel. However, we do not impose how they should feel because that is their personal freedom. We merely strive to provide them with the conditions for them to experience. This is why the concept of “responses” is essential. As architects, our job is not to dictate their responses but to provide the conditions that make it possible for them to respond. Our creation is based on providing a physical foundation, and within this physical condition, if we do it appropriately, they may have their own emotional responses. However, these responses will vary from individual to individual. If I want them to feel in a specific way, I believe it goes against humanity. Each person’s experience is unique, and everyone is different.

Jack Young:

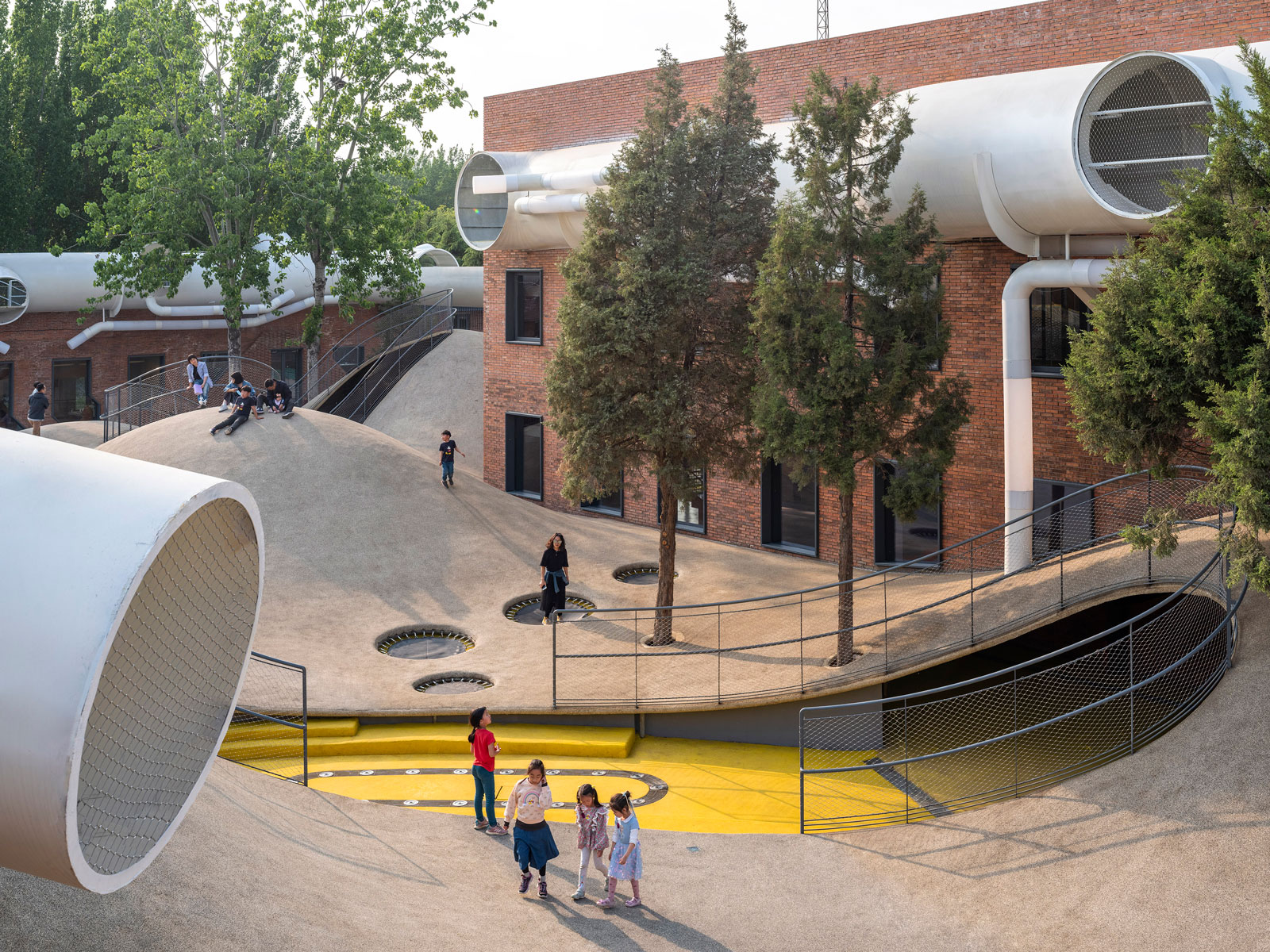

I believe this is crucial; architecture should respond to human emotions. It is something I am very interested in, and it is also a part of art. Architecture has the potential to allow people to utilize or enhance their senses while experiencing the building itself. I find it fascinating how to achieve this and how to incorporate these potential sensory experiences, especially when introducing interactivity into such projects. If we try to exaggerate these senses, it involves balance, particularly in terms of the balanced development of children. That’s why we designed hills in the project. I think the identity of this architecture is related to activities, not just the appearance. It is actually related to participation, so children bring vitality to this project, and the presence of children is necessary for the building to be complete. I think that’s the simple truth.

Zhang Di:

The growth stage of children is indeed crucial as it provides them with direct and explicit perceptions and emotions. I do not want to impose too many restrictions on them, such as telling them they must have cartoon characters or only accept primary colors or strong colors. Because I believe children also have aesthetics, and aesthetics can be trained and nurtured. Therefore, we just hope to present beauty to them in different ways and accept their unique ways of experiencing and understanding based on their own states. I consider this as the social responsibility of an architect. Therefore, the initial theme of our project was “returning to the neighborhood,” like the feeling of streets in childhood. When we first discussed with the clients, as they were from the post-90s generation and we were from the post-80s generation, I asked them about their childhood memories. I shared that my childhood memories were of those big concrete pipes on the street where we could crawl inside, the mounds of soil to climb on, digging holes, and running onto other people’s roofs and jumping into their yards. For me, these were intense childhood memories, whether direct or indirect, they provided me with feelings and responses.

Jack Young:

Understanding body language allows you to comprehend other signals and implications that people give, especially in this project where you can see that children are actually the best part. The most exciting thing is

observing those kids, who may only be four years old, successfully climb these small hills. They are not afraid, and they don’t fall. They demonstrate this ability, which perhaps even their parents were not aware they possessed at such a young age. So, in this sense, in a very safe environment, we let them freely experiment. The natural goal is to overcome obstacles.

Zhang Di:

My daughter has always been the most timid girl, but when she was four years old, she showed the instinct to climb. I remember when we were studying to become registered architects in the UK, the first lesson, the first page said, “To become an excellent architect, you need a good client.” This signifies mutual trust and the importance of providing opportunities. Only when you can obtain such an opportunity and satisfy the client’s needs or even exceed their expectations, can you become an outstanding architect. I think this project is a very rare opportunity.

Jack Young:

I believe the creation of architects should center around people, and architecture should address human emotions. I consider this as a significant social responsibility for architects.

Zhang Di:

Every time we undertake an architectural project, or when our architecture comes to life, I adhere to one principle: we do not repeat ourselves. Many people may contact us, hoping to have a similar building to our previous works because they think it was highly effective and want to replicate it. But I strongly oppose this. I tell them that I can do better, something more suitable for their needs. I say to them, have confidence in yourself and have confidence in your site. Since you have chosen us, you can find different methods. This doesn’t mean it will be better; it means it will be different because everyone’s needs are unique. I think this is a fundamental bottom line.